Guitar Bar Chords

Guitar bar chords are more correctly spelled 'barre' chords. For the ease of writing however, I will adopt the easier spelling of 'bar' chords. For the beginner guitarist, bar chords are often seen as a bit of an unnecessary and often painful and awkward experience to learn let alone master. The truth is though, like all aspects of learning to play any instrument, with patience and diligent practice it all gets so much easier. Having the ability to be able to play bar chords is important if you truly want to progress to any decent level of playing the guitar, so, if that is what you want, persevere and keep practicing in order to get them under your belt. Remember, like all things worth having, there are no short cuts so stick with it and be patient.

Website owners and Bloggers

You're free to copy and use my charts on your website or blog if you choose. All I ask in return is that you leave the URL of this site intact on those charts that have it and please show your appreciation to all my time and hard work by linking back here, thank you.

To go straight to the guitar bar chords charts just click the relevant links below, or for more information on the construction of chords in general please read on.

Note: The names below relate to the 'open' chord shape equivalent of the bar chords in the same chart. For example, the first chart below, the 'A major chord shape', means that the bar chords in that chart are taken from the open A major chord shape. You will see on all of the bar chord charts that the very first chord shape is always an open chord and not a bar chord at all. The rest of the chords after this first open chord are all the same basic open chord shape but with the bar added behind in order to keep the chord's structure correct.

This is a good way to learn to help you to understand and to relate things on the fretboard.

Common Guitar Bar Chords

Less Common Guitar Bar Chords

Generally speaking, for the ease of understanding, most bar chords could be seen as being taken from 'open' chords. Therefore, bar chords may be best understood as a specific open chord being played using any number of the second, third and fourth fingers thus leaving the index finger free to hold down all or some of the strings (half bar) behind the regular open chord shape being played. I've decided to illustrate them this way as I think it is more helpful to beginners to understand music with regard to the chromatic scale (discussed further down).

Guitar bar chords can also be seen just as they are. For example; major seven shape bar chords, dominant seven bar chords or minor seven bar chords etc.

Either way, having the ability to play bar chords well really does make you a far better guitarist than just sticking with the much easier to play open chords. In fact, most styles of guitar playing require you to be able to play bar chords at some point or another. This is true of rock, pop, country, jazz, blues and classical guitar styles among others. Only being able to play open chords is totally fine if that's all you want to do and you're happy with that of course. If however you want to progress as a guitarist and be able to play a wider variety of popular songs in different keys, whether they're rock, pop, country, jazz, blues or classical pieces, then you really do need to get to grips with them.

Bar chords really do open up the entire neck to you. For each basic open chord shape there are potentially eleven new chords (one for each key) making twelve in total before the chord's tonal centre repeats itself at the twelfth fret. This means that from the first bar chord taken from its related open chord shape there are another ten bar chords, each one in a different key and all played without having to change the first bar chord shape at all. Easy!

This is achieved by simply sliding any bar chord up or down the neck to a different fret position. As already mentioned, the original open chord shape will have to be played using any number of the other three fingers of your hand, i.e. the middle, ring and/or little (pinkie) finger thus freeing up the index finger to be used for the bar.

Note: The table below illustrates the correct finger guide to use for the guitar bar chords that follow and for all chord and scale charts for this site and for music in general in fact. Note also the '0' showing an open string to be played as well as an 'X' to indicate that particular string not to be played.

The finger reference for playing the guitar is;

1=index finger, 2=middle finger, 3=ring finger,

4=little (pinkie) finger

O = an open string to be played

X = a string not to be played

As always for this website the red notes are the root notes. Root notes give a chord its name, tonal centre and over all sound. The root note is the note that any chord is built upon. It is very good practice to remember these root notes in relation to the chord while you learn each new chord shape. In time you'll be able to run through a scale starting from any root note while knowing what chord or chords that scale relates to.

Practice!

To understand this fully we have to go back to the beginning and take a look at the chromatic scale which is illustrated below and also discussed in more detail on the guitar lessons for beginners page.

Now, if you look at the chromatic scale seen below it relates to notes. The point to remember is that it also relates to chords.

The Chromatic Scale

A, A#/Bb, B, C, C#/Db, D, D#/Eb, E, F, F#/Gb, G, G#/Ab - repeat

Remember, A# is the same as Bb, C# is the same as Db, D# the same as Eb, F# as Gb and G# as Ab.

Memorise the above!

So, if we start with the simple chord of E minor (Em) for example and then move that basic chord shape up just one fret we will come to the next note (and chord when playing chords) up from E on the chromatic scale chart above which is F. When playing chords this note represents the root note. The root note of any chord is known instantly by the name of the chord. For example, the root note of E minor is E of course. In fact, the note of E is the root note of any E chord whether a minor, major, or dominant seven etc. Likewise, F is the root note of any F chord also and so on and so forth with every one of the twelve notes of the musical scale also known as the chromatic scale.

When moving open chords up the neck of the guitar we have to replace the nut position at the end of the neck with our index finger thus creating a bar. If we don't then it is not a correct chord. It is still a chord as such though because the term 'chord' implies a 'string' of notes. If we don't make a bar with the index finger however it becomes an obscure chord with no musical definition and just sounds naff. Adding the bar keeps the structure of the chord correct with regard to intervals (spaces between the notes). This new bar chord has the same structure as the original open chord and therefore the same overall sound. The difference is, it will be in a different key because the root note has changed position and is now a different note entirely. The name of that new root note indicates the note name of the new bar chord. E, A or C etc. This principle applies to all chords.

Understanding Chord Construction

The construction of all chords including the following guitar bar chords all relate to the major scale. To understand this fully you'll need to have some basic knowledge of the major scale. All chords are formed from intervals (the spaces between the notes) of the major scale. What this basically means is that certain notes of the major scale or notes that relate to the major scale are played on top (stacked) of one another as opposed to being played one after the other as in a scale or melody.

Using the simple chord of A major as an example we can determine that the notes in the chord of A major are A, C#, and E. To relate these notes to the major scale we can establish that the first note of the A major scale is A, C# is the third note and E is the fifth note of the A major scale respectively. This is written as 1, 3, 5 and is the construction or formation of the chord of A major which relates to the A major scale as it only contains the 1st, 3rd and 5th notes of the A major scale. Yes there are more than three notes or strings actually played when A major is strummed, but the only actual musical notes that are played are in fact only those three notes i.e. A, C#, and E.

Because the chord of A major, just as one example, only contains three notes it is known as a triad, meaning three of course. Any chord's construction is also known as the 'spelling' of a chord.

Incidentally, the first note of any scale is also known as the 'tonic' or sometimes the 'root note', although the term 'root note' is more accurately related to the tonal centre of a chord as opposed to a scale.

If we took another chord as an example such as A7, also written as A dominant 7 (Adom7), we would see that the spelling here would be 1, 3, 5, b7. This is because the dominant 7 chord contains four musical notes so it is not a triad like the previously discussed A major chord. Like the major triad chord though it does contain the 1st 3rd and 5th notes of the major scale, but it also contains an additional note in its construction which is the b7. The b7 is the flattened 7th note of the major scale which means it has been lowered by one semi-tone (one half-step).

So, the 7th note of the A major scale is dropped one semi-tone (one fret) and played alongside the other notes of the A major chord thus creating a different chord - A7 respectively. This is where the Dominant 7 chord gets its name of course, the b7 (flat 7) and overall characteristic sound. The b7 note in the key of A is G. This is written in the spelling for this chord further down this page.

The spelling (construction) for each of the guitar bar chords that follow can be seen above each chord chart that follows to clearly establish each chord's individual construction and relationship with the major scale.

Note: All guitar bar chords will have an associated open chord from which the bar chords are formed. This open chord voicing will also be illustrated at the beginning of each new chord shape chart to clearly show how the subsequent bar chords are generated. For lots more chords other than just bar chords take a look at the guitar chords charts.

Back To TopA Major Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Charts #1 & 2

Major Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th - (major triad)

This is a major triad as it contains a third (3rd) making it major as opposed to a b3rd (minor) and only three notes which makes it a triad.

These guitar bar chords are taken from the open A major chord that we all know and play. The A major open chord is one of the very first guitar chords for beginners. If you look at the root notes in red you'll see that they continue in the same order as the chromatic scale discussed above. The root notes also give each chord its note name.

These chords go up fret by fret in the order of the chromatic scale below. This principle applies to all the guitar bar chords charts shown.

A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G# and back to A.

A Major Open Chord Shape Continued...

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #2

The chart below is a continuation of the chart above. Again, you can see the root notes continuing up the chromatic scale fret by fret. The very last chord here (G#) is the chord before resolving back to the original first chord played which is the chord of A major. It just happens to be played higher up the neck and with a bar of course. This could be seen as an octave chord (the same chord as the starting chord - A) This is just like an octave in a scale which is the same note as the first note of any scale (called a 'tonic') and is reached after a certain number of notes played within the scale but is higher in pitch. All guitar bar chords work in this way. This is how we can easily learn more chords just by simply adding a bar, sliding up the neck fret by fret and applying the chromatic scale to give us the root note and chord name.

Back To TopA Minor Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Charts #3 & 4

Minor Chord Spelling - 1st, b3rd, 5th - (minor triad)

A minor triad as it contains a flat third (b3rd) making it minor and only three notes making it a triad.

These guitar bar chords are taken from the open A minor chord. The same principle applies to these bar chords as with the previous charts, and all bar chords in fact, where the root notes in red continue in the same order as the chromatic scale previously discussed. These chords therefore go up chromatically fret-by-fret. - A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G# and back to A.

As before, the root notes also give each chord its note name.

Back To TopA Minor Open Chord Shape Continued...

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #4

Again, the very last chord here (G#) is the chord before resolving back to the original first open chord of A minor. So if you were to continue on past the G#, the next bar chord would be A minor because A comes after G# as seen in the chromatic scale - A, A#, B, C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G# and then back to A, then A# and so on etc.

The A minor bar chord played at the twelfth fret after the G# below is just another version of the open A minor chord at the beginning but played higher up the neck and with a bar so it keeps the correct chord structure. Take the bar away and see what it sounds like. Replace the bar and you will hear the A chord immediately.

A Dominant 7 (A7) Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Charts #5 & 6

Dominant Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th, b7th

This can be seen as a major (the 3rd is played) with and added flat seventh note of the major scale.

This open A7 chord shape and its related bar chords tend to be mainly always played in blues guitar where they occupy the second and third chords to be played in a standard I, IV, V blues chord progression, in which case they would be known as the IV and V chords respectively. The I, IV, V blues chord progression is discussed further and also demonstrated at the blues guitar chords page and also the blues guitar instruction page.

Adom7 Open Chord Shape Continued...

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #6

As with all these charts, the very last chord on the chart below is on the eleventh fret which is obviously one fret before the twelfth. The twelfth fret on any string is the same note as that same string when the string is played 'open'. Likewise, any chord played on the twelfth fret has the same name as the 'open' version of the same chord. Therefore, the next chord that would be played one fret up after the last chord below would also be A7 - the same as the very first 'open' chord on the chart above. This applies to all chords and all six strings of course.

Back To TopA Major 7 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #7

Major Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th

This can be seen as a major (the 3rd note of the major scale is played) with an added seventh note of the major scale.

This guitar bar chords chart shows the major seventh. For me personally, the major seventh is probably one of the nicest sounding of all the major chords. The major seventh voicing has a warm, happy, up-beat sound that is often used in jazz, fusion and other musical styles such as bossa nova which was created by the great composer Antonio Carlos Jobim.

The first chord here, the open A major 7 chord generally leaves out the open bottom E string as it's often emits too much bass although it wouldn't necessarily be incorrect as the note of E is played within that particular chord. This same principle applies to all the other bar chords here. For example, the second bar chord below can play the 'F' on the bottom E string (index finger fretted) or not, and so on and so forth with the rest of the chords here.

Back To TopA Minor 7 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #8

Minor Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, b3rd, 5th, b7th

The minor seventh chord has both the flat third (b3rd) note of the major scale and also the flat seventh (b7th) note of the major scale in its construction.

The minor seventh takes the standard minor chord triad voicing and adds one extra note, the flat seventh (b7th). Alternatively, the minor seventh can be seen as taking the dominant seventh chord and adding a minor third (flattened third note of the major scale) as opposed to playing the 3rd of the major scale. The minor seventh chord adds a little bit of extra flavour to the regular minor chord voicing.

Back To TopE Major Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #9

Major Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th - (major triad)

These bar chords are all taken from the open E major chord which is one of the very first guitar chords for beginners that you will learn.

E major, just like A major, is a major triad as it contains a major third (3rd) making it a major chord as opposed to a minor chord which would contain a flat third (b3rd) which is the third note of the major scale dropped down one semi-tone or one fret. Major triads also contain only three notes each in total which gives them their characteristic name (triad means three).

E Major Open Chord Shape Continued...

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #10

As with all the guitar bar chord charts on this page, the last chord shape below is the chord played before resolving back to the E major chord that we originally took these particular bar chords from. I.E. D# comes before E on the chromatic scale doesn't it, so if we slide the very last bar chord shape below (D#) up one fret it becomes E major. It's just played higher but would still be the chord of E major as it would contain the same notes - E, B, G#/Ab. It would of course be barred however instead of played 'open'.

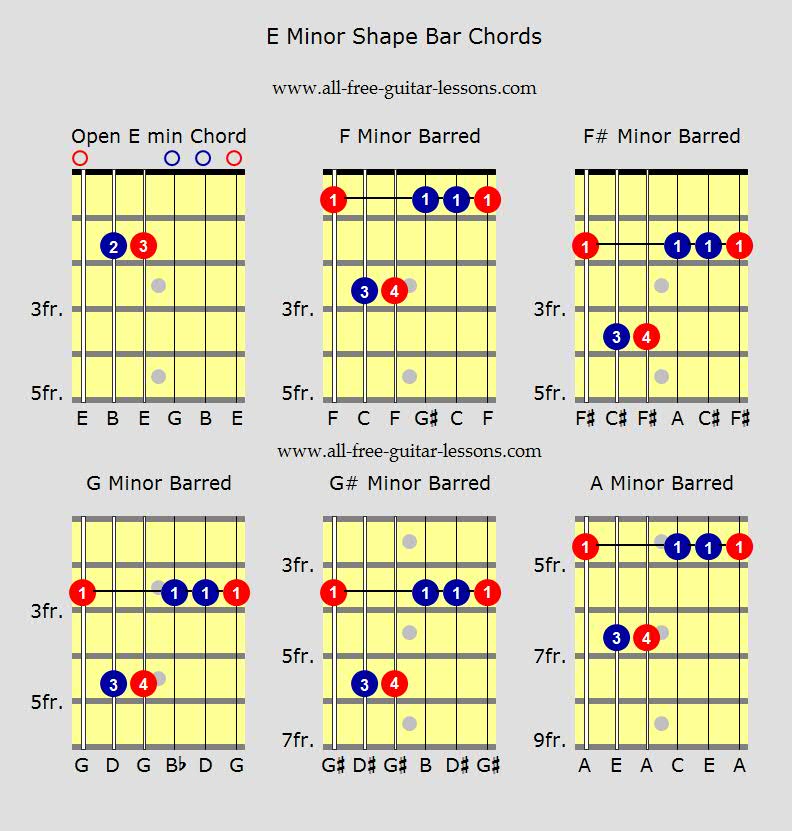

Back To TopE Minor Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #11

Minor Chord Spelling - 1st, b3rd, 5th - (minor triad)

These bar chords are all taken from the very easy to play open E minor chord which is another one of the very first guitar chords that you will learn when first picking up the guitar.

E minor, just like A minor, is a minor triad as it contains a minor third or flat third (b3rd) making it a minor chord as opposed to a major chord which would contain a third (3rd) which is the third note of the major scale. As we have already established, minor triads also contain only three notes each in total which gives them their characteristic name of 'triad' which refers to the number three.

E Dominant 7 (E7) Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #12

Dominant Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th, b7th

This can be seen as a major (the 3rd is played) with and added flat seventh note of the major scale.

Like the A7 chord shape and its associated bar chords further up this page, this well-known and well played 'open' E7 and related bar chords are generally mainly played in blues guitar. Unlike the previously mentioned A7 chord shape though, this shape tends to take the precedence of the I chord in the standard I, IV, V blues chord progression, which, as previously mentioned, is discussed in more detail and also demonstrated at both the blues guitar chords page and the blues guitar instruction page.

An easier way to play this chord is to simply leave out the 4th finger note. Adding it again randomly gives an additional bit of colour to the chord and the chord progression. This is particularly useful and very common practice for blues guitar.

E Major 7 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #13

Major Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th

This can be seen as a major (the 3rd note of the major scale is played) with an added seventh note of the major scale.

A nice warm, jazzy sounding chord, the major seventh is one of my favourites. This bar chord shape differs from the major seventh further up the page though which is taken from the A major seven open chord. This version, taken from the open E major seven chord shape, is probably not as commonly used as the A shape version previously illustrated. The chord shape shown here therefore gives a slightly different sound to the previously mentioned chord and so offers another approach to playing this nice sounding chord.

As you can see, the root note on the top E string is indicated not to be played. Although it is a root note and therefore musically correct for it to be played, it does sound a little high and a bit out of place I think you might agree. Play it with and without that high root note and see what you think. Like all things musical though, it's up to you if you choose to play it or not.

Back To TopE Minor 7 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #14

Minor Seventh Chord Spelling - 1st, b3rd, 5th, b7th

Both the flat third (b3rd) note and the flat seventh (b7th) note of the major scale are included in the minor seventh chord's construction.

This guitar bar chord shape is a big open shape that tests the stretching ability of the fret board hand for beginners. The minor seventh chord adds the b7th to the regular minor chord's construction. It can also be seen that the dominant seventh chord adds the minor third. It could effectively therefore also be named the 'minor dominant seventh'. The minor seventh adds a little bit of extra flavour to the standard minor chord voicing.

Back To TopC Major Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #15

Major Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th - (major triad)

This guitar bar chord is taken from the open C major chord as seen in the first chord shape below. Generally speaking, you wouldn't play the lowest bass note on any of these chords (the note marked X) particularly if you were playing along with a bass guitarist who would be picking up the bass note there. It would not be incorrect to play it though as it is a root note so once again the choice is yours.

Like all major chords this is a major triad as it contains only three notes in total. This makes it a triad (triad meaning three) and a major third (3rd) which makes it a major chord as opposed to a flat third (b3rd) which would make it a minor chord.

As with all the major chord voicings the sound is more 'happy' and up beat when compared to the minor chord voicings.

Note: See the third chart further down for a slightly different way to play this bar chord shape using the half-bar.

Depending on what feels the most comfortable to you, the above bar chord can be played with a half bar as seen below. After the last chord on the chart below (F major) just continue fret by fret up the guitar neck as with all the previous charts.

Back To TopC Major 7 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #16

Major 7 Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th

This is another way to play the much loved major seventh chord. One thing I would like to mention again is that it is down to you much of the time whether or not to play any strings marked with an X. The suggestion is obviously not to play them, but if you personally think it sounds ok to play them then that is fine. A good rule of thumb however is whether or not these X marked notes/strings are indeed a root note or whether they are a part of the chord's structure. For example, with the bar chord shapes below the open bottom E string (that is marked X) could technically be played whenever an E is seen and therefore played in the rest of the chord. It comes down to personal preference and whether or not you want more bass to be heard.

Note: As you can see, this bar chord shape uses the half-bar. The half-bar is much easier to play for beginners than the more difficult full-bar as seen is most of the other bar chord charts.

Back To TopA Major Sixth Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #17

Major Sixth Chord Spelling - 1st, 3rd, 5th and 6th

The major sixth adds the sixth note of the major scale to the regular major triad as illustrated in the first (A major) and sixth (E Major) guitar bar chords charts. The major sixth is a classic chord often used for the ending of many songs in many different genres. The first open chord shape below (A maj6) couldn't be easier to play and is a great first chord for beginners to get used to playing the bar.

The rest of the bar chords in this particular chord shape are unusual in the fact that they use the third finger (ring finger) to hold down the bar leaving the first finger (index finger) to play the other note in the chord. This may feel a little awkward at first, especially for beginners, but it will get a lot easier over time with continued practice.

Back To TopA Suspended 2 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #18

Suspended 2 Chord Spelling - 1st, 2nd, 5th

Technically speaking, suspended chords are neither major nor minor chords because they have no third degree (third note of the major scale). Suspended chords are therefore rather airy with no obvious direction and only identified by the context of the other chords in the progression. They are often used in ballads and slow tempo tunes where they help to create a sense of harmonic ambiguity or uncertainty.

Back To TopD Suspended 2 Open Chord Shape

Guitar Bar Chords Chart #19

Suspended 2 Chord Spelling - 1st, 2nd, 5th

These bar chords utilize the half-bar. Traditionally, suspended chords are used to hide the identity of a major chord as they are neither major nor minor due to the lack of a third degree (3rd note of the major scale) in their construction. Therefore, when suspended chords are played before a similar major chord voicing, their lack of identity creates tension that resolves when the following major chord is played.

The first open chord below is a nice easy one for beginners and produces a full resonant sound due to the two open strings out of only four notes. The sixth bar chord shape below (Gsus2) plays the open A string as A is in that chord's construction. It is of course optional whether or not you do choose to play it.

The second bar chord shape below (Asus2) plays the open A string which is that chord's root note. Again, whether you choose to play it or not is your choice.

You will have probably noticed that there is more than one way to play a specific chord. If we take the C major chord illustrated further up (guitar bar chords chart #15) as one example, you can see that C major is also played utilising the open A major chord shape in the very first diagram near the top of this page. That version is played behind the third fret but is still C major as it contains exactly the same musical notes but they are played in a different place. This happens all the time on the guitar fret board and can be seen more clearly with different versions of the same chords being illustrated on the guitar chords charts.

As I have already said but I can't emphasise enough, learn to play bar chords well if you're serious about playing the guitar. They are a necessary evil that will undoubtedly get much easier over time until one day you won't have to think about them at all.

Back To TopGuitar Chords Charts | Guitar Chords for Beginners | Home

Blues Guitar Chords | Guitar Scales Charts | Jazz Guitar Scales